Blob-like + Encrusting

Sea Pork

Description

Sea pork tunicates grow as plate-like, irregular or spherical masses attached to rocks or shells. Colonies are hard and very smooth. The surface is covered with circular groups of pores that give it a starred appearance. It is pale bluish to sea green in coloration. When colonies wash ashore, they bleach white and may look like slices of salt pork or fat back. Sea pork colonies may be over an inch thick and more than 12 inches in diameter.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. This tunicate can form a large, hard rubbery mat on the surface of clam bags or cover netting.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. This tunicate can be difficult to remove from the bag or cover net surface.

Purple Acorn Barnacle

Description

The purple acorn barnacle ranges from Massachusetts to the Gulf of Mexico and the West Indies. This small barnacle, like most barnacles, is sedentary, settling on almost any hard substrate, including rocks, pilings, shells, debris, mangrove roots, and crabs and cementing itself there for the duration of its life. All barnacles are also filter feeders, sticking their feather-like legs (cirri) out through the top to catch passing plankton. The purple acorn is conical, with light purple stripes running the length of each plate. It has four movable plates that close the top hole when its not feeding to protect the animal. Dead barnacles are identified by the lack of these movable plates. The name “acorn” refers to the lack of a stalk in this barnacle species. It can reach almost 1 inch in height.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Barnacles can have a two-fold effect on clams. As a filter or suspension feeder, barnacles can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. They can also attach to cover netting and to the clam shells themselves. This can result in mechanical interference with clams, preventing them from opening up, feeding or burying. Fouling on the shells can make clams less desirable for marketing.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Fouling of barnacles on clams within the bag is usually a result of the bag not being able to bury completely in the bottom substrate. A grower should limit the use of lease bottoms that are excessively hard or contain shell hash during periods of peak barnacle sets. Generally barnacles do not set directly on the soft clam bag mesh. In most cases, they are found on oyster shells attached to the bag. However, clam bags dipped in net coatings, result in a stiffer bag surface and may allow for settlement of barnacles. Gloves are necessary when handling bags covered with barnacles as the shells are sharp.

Ivory Barnacle

Description

The ivory barnacle is the most common barnacle found in the Gulf of Mexico and southeastern U.S., growing on oysters, rocks, pilings, and mangrove roots close to the low tide line. It is comprised of 2 pairs of plates overlapping 1 or 2 unpaired plates. There are two pairs of grooved plates on top that move to allow the feeding apparatus to extend. The shells are entirely white and, like other barnacles, this barnacle is a filter feeder. It is also like the purple acorn barnacle, as it does not have a stalk. It is a rather large barnacle, reaching 3 inches in length, and up to 1 inch in height.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Barnacles can have a two-fold effect on clams. As a filter or suspension feeder, barnacles can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. They can also attach to cover netting and to the clam shells themselves. This can result in mechanical interference with clams, preventing them from opening up, feeding or burying. Fouling on the shells can make clams less desirable for marketing.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Fouling of barnacles on clams within the bag is usually a result of the bag not being able to bury completely in the bottom substrate. A grower should limit the use of lease bottoms that are excessively hard or contain shell hash during periods of peak barnacle sets. Generally barnacles do not set directly on the soft clam bag mesh. In most cases, they are found on oyster shells attached to the bag. However, clam bags dipped in net coatings, result in a stiffer bag surface and may allow for settlement of barnacles. Gloves are necessary when handling bags covered with barnacles as the shells are sharp.

Striped Barnacle

Description

The striped barnacle has a similar appearance to the purple acorn barnacle. It also has a similar range, though it does not extend nearly as far north, commonly found in the shallow waters of the southeastern U.S. It has a rough shell, with a triangular opening covered by deep-seated closing plates. It has two sets of 4 or 5 dark purple lines down each plate. As in the other “acorn”-type barnacles, it is a sedentary animal that filter feeds using feather-like feet (cirri) and is not perched upon a stalk. This barnacle reaches 1 inch in height.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Barnacles can have a two-fold effect on clams. As a filter or suspension feeder, barnacles can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. They can also attach to cover netting and to the clam shells themselves. This can result in mechanical interference with clams, preventing them from opening up, feeding or burying. Fouling on the shells can make clams less desirable for marketing.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Fouling of barnacles on clams within the bag is usually a result of the bag not being able to bury completely in the bottom substrate. A grower should limit the use of lease bottoms that are excessively hard or contain shell hash during periods of peak barnacle sets. Generally barnacles do not set directly on the soft clam bag mesh. In most cases, they are found on oyster shells attached to the bag. However, clam bags dipped in net coatings, result in a stiffer bag surface and may allow for settlement of barnacles. Gloves are necessary when handling bags covered with barnacles as the shells are sharp.

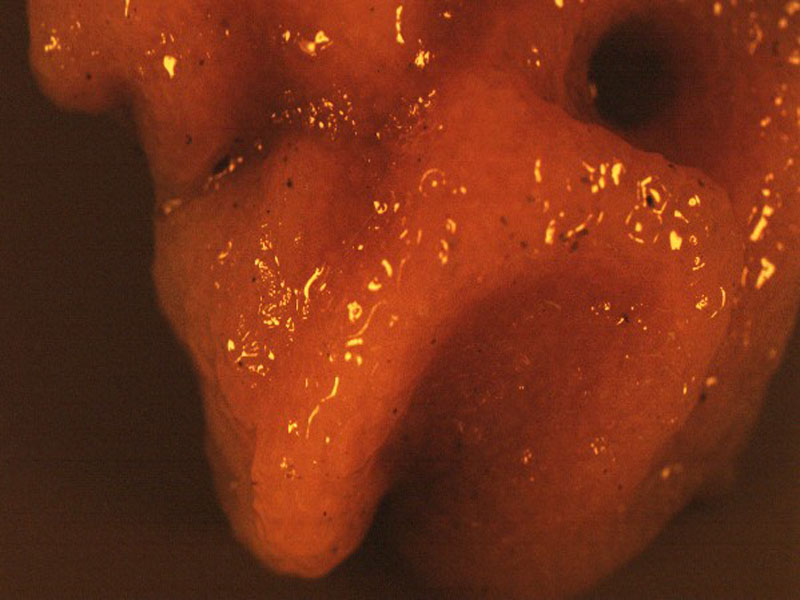

Pacific Colonial Tunicate

Description

The Pacific colonial tunicate is native to Japan but was accidentally introduced to California in the late 1970s. By the 1980s it had become very common in estuaries throughout New England. Pacific colonial tunicates live on eelgrass, seaweeds, pilings, and other hard substrates in shallow waters. Color of Pacific colonial tunicates is variable, but they are usually bright orange. Individual zooids (structures of individual animals) are arranged in meandering rows. Pacific colonial tunicates grow to over 10 inches in diameter and about 1/8 inch thick.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. The colonial tunicate could potentially settle and cover clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

The Pacific colonial tunicate has not been sighted in the Suwannee Sound area, but has recently been found in Tampa Bay. If a suspected tunicate colony is found, growers should report to the Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program at 877-STOP-ANS or on the Internet at the website: http://nas.er.usgs.gov. If possible, save samples by freezing.

Golden Star Tunicate

Description

The golden star tunicate grows on eelgrass, seaweeds, pilings and other hard substrates. Colonies are dark brown, green, or purple; while the star-shaped clusters of tiny individual zooids (structures of individual animals) are each 1/16 inches long and yellow or white in coloration. Golden star colonies grow to over 8 inches in diameter and 1/8th inch thick.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. The golden star tunicate is not as commonly found as the white crust tunicate, but this colonial tunicate can potentially cover clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags.

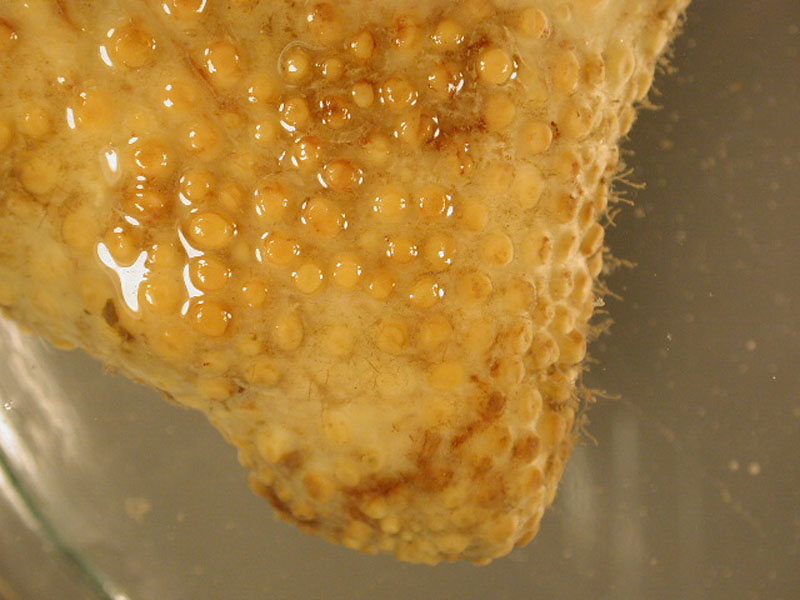

Yellow Boring Sponge

Description

The yellow boring sponge is found growing on rocks, shells, and corals in the subtidal zone and may overgrow its substrate entirely. The lobe-shaped, hard sponge appears bright yellow with pimple-like pores. Dried specimens appear woody and brown with dots surrounded by faint circles. Large specimens can measure up to 3 feet across and 1½ feet high, while individuals are less than 1/8 inch in width.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Larvae of this sponge settle on shells and develop into tiny sponges. By secreting sulfuric acid, the sponge bores into the calcareous shell of mollusks (oysters and clams). Affected shells are riddled with small holes (about 1/8”), creating a honeycomb of tunnels. The shell can be weakened to the point of disintegration, resulting in the death of the mollusk.

- FOE

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

This sponge may be controlled by exposure to sun in early stages of development.

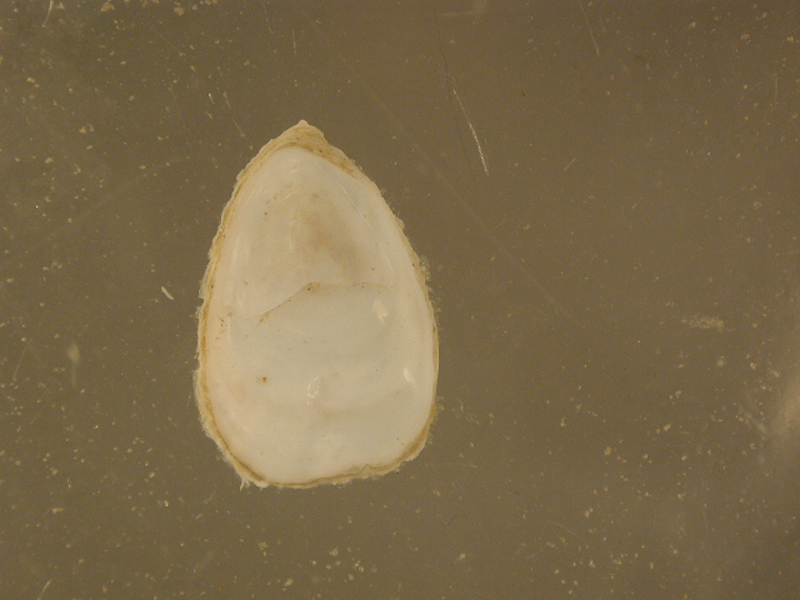

White Crust

Description

White crust tunicates (sea squirts) resemble a splash of white paint on firm surfaces, including rock rubble and seaweeds. Colonies look smooth but feel gritty due to calcareous spicules (dart-like or needle-like structures supporting the tissue of the tunicate). When the colony is damaged, it releases sulfuric acid and vanadium, which are toxic to most marine organisms. White crust is only 1/10 of an inch in thickness, but can exceed 4-8 inches in diameter.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. This colonial tunicate can cover large surface areas of hard bottom substrate, as well as clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. This tunicate can be difficult to remove from the bag or cover net surface.

Frog Egg Tunicate

Description

Frog egg tunicates (sea squirts) grow on hard objects, such as rocks, but will also grow on other fouling organisms, such as hydroids and bryozoans. Colonies are thin, gelatinous, and slimy. The body of an individual tunicate is greenish-grey and is imbedded in a transparent structure, making the colony resemble an amphibian egg mass. Frog egg tunicates are 1/10 of an inch thick and 4 inches or more in diameter.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. This colonial tunicate can cover large surface areas of hard bottom substrate, as well as clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. This tunicate can be difficult to remove from the bag or cover net surface.

Taxonomy

- Kingdom:Animalia

- Phylum: CHORDATA

- SubPhylum: Urochordata

- Class: Ascidiacea

- Order: Aplousobranchia

- Family: Didemnidae

- Genus: Diplosoma

- Species: listerianum

Orange Tunicate, Mangrove Tunicate

Description

The orange or mangrove tunicate grows attached to mangrove roots, turtle grass and other surfaces. Individual zooids (bodies of individual animals) occur in clumps, joined at their bases by a “root.” They are transparent with orange markings on the siphons. Individual orange tunicates are about 1 inch long.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. Each individual "polyp" of this colonial tunicate is a hungry mouth. The tunicate can attach by its “root” to clam bags and can be a major fouler.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. Individual squirts can be manually removed from the bag surface by hand or brush and will not reattach.

Sea Liver

Description

The sea liver tunicate is a colonial animal which can be very extensive and thickly cover substrates, such as docks. Colonies are purple, with large, rubbery, slippery lobes, resembling liver. It may turn white in the winter. The tiny brownish zooids (structures of individual animals), embedded in the colony, are arranged in groups of about 1/10 of an inch in diameter. Juvenile crabs often occupy the folds and creases of colonies. The surface of sea liver colonies is rarely fouled by other organisms.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. The sea liver tunicate is not as commonly found as the white crust tunicate, but this colonial tunicate can potentially cover clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags.

Taxonomy

- Kingdom:Animalia

- Phylum: CHORDATA

- SubPhylum: Urochordata

- Class: Ascidiacea

- Order: Aplousobranchia

- Family: Polycitoridae

- Genus: Eudistoma

- Species: hepaticum

Bread Sponge

Description

The bread sponge is found on protected undersides of stones, pilings, and other hard substrates, including animals, from the low-tide line to waters more than 200 feet deep. It thrives in harbors and estuaries where it is tolerant of muddy and brackish conditions. It is often found intertwined with hydroids and algae. This sponge has a thin crust that can appear yellow, olive, or beige and can vary in form from cushion-like to gnarled, finger-like branches. The sponge pores are prominent with tiny conical projections which create a texture resembling bread crumbs. The bread sponge can grow 12 inches wide and 2 inches high.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

This sponge can form mats and potentially spread over the surface of clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. Air drying would be the only effective means of removing this sponge from clam bags.

Taxonomy

- Kingdom:Animalia

- Phylum: PORIFERA

- SubPhylum:

- Class: Demospongiae

- Order: Halichondrida

- Family: Halichondridae

- Genus: Halichondria

- Species: bowerbanki

Sun Sponge

Description

The sun sponge is a low growing sponge that can be found in shallow waters with direct sunlight. It occurs intertidally anchored on shell debris in sand, oysters, and other hard objects, and is tolerant of short periods of air exposure. The sponge may exceed 16 inches in diameter and appear as encrusting sheets with numerous erect, rough, finger-like projections. Coloration can vary from light yellow with olive green tints in sunny areas to deep orange or reddish-orange in shaded areas. The sponge’s configuration offers habitat to numerous smaller animals like shrimps, crabs, and brittle stars.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

This sponge can form mats and potentially spread over the surface of clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. Air drying for at least 24 hours would be the only effective means of removing this sponge from clam bags.

Garlic Sponge

Description

The garlic sponge is found on pilings and seagrasses in shallow waters. It often is seen surrounding individual blades of grass, growing to fist size. This sponge can appear yellow, blue, or green-gray externally, and is tan internally. Its shape can be amorphous, irregular, and sometimes mound-like with lobed edges. The surface is usually smooth with conspicuous, randomly distributed pores. When broken, it emits a strong odor of garlic, hence its common name. The garlic sponge can reach a height of 8 inches.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

This sponge can form mats and potentially spread over the surface of clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. Air drying would be the only effective means of removing this sponge from clam bags.

Taxonomy

- Kingdom:Animalia

- Phylum: PORIFERA

- SubPhylum:

- Class: Demospongiae

- Order: Poecilosclerida

- Family: Tedaniidae

- Genus: Lissodendoryx

- Species: isodictyalis

Sea Mat

Description

The common sea mat is a calcareous, encrusting bryozoan that forms a white, lacy mat on rocks, shells, and other hard substrates, and is very common in shallow areas along the Florida coast and the Gulf of Mexico. It is a colonial animal with colonies reaching many inches in length. The rectangular body chamber of individual animals is structurally continuous with that of others in the colony, with each animal enclosed in its own box-like exoskeleton. The feeding apparatus is contained within this box, and is extended to feed upon passing plankton.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Bryozoans are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. This bryozoan can also attach to clam shell surfaces, making the clam undesirable for market.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

If the clam bag and clams themselves are completely buried in the bottom substrate, fouling and food competition should not occur.

Red Beard Sponge

Description

The red beard sponge is found on rocks, pilings, oysters, shells, and other hard objects in protected bays and estuaries below the low-tide line. This sponge appears bright orange to red and dried specimens are often brown. It varies from a thin encrusting layer less than 1/8 inch wide covering a few square inches to 8 inches high and 8 inches wide with many branches. Its knobby, multi-branched form makes identification easy.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

This sponge can form mats and potentially spread over the surface of clam bags and cover netting.

- FOE

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. Air drying would be the only effective means of removing this sponge from clam bags.

Taxonomy

- Kingdom:Animalia

- Phylum: PORIFERA

- SubPhylum:

- Class: Demospongiae

- Order: Poecilosclerida

- Family: Clathriidae

- Genus: Microciona

- Species: prolifera

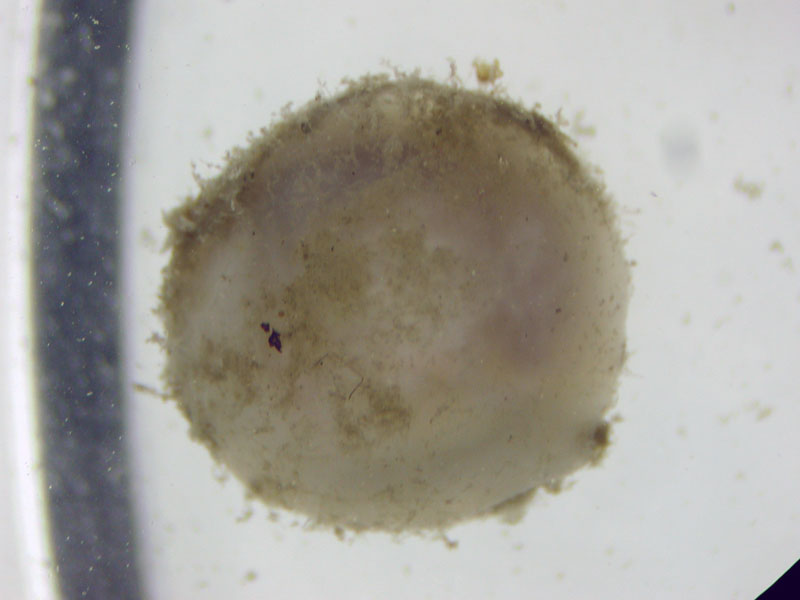

Sea Grape

Description

Sea grape tunicates (sea squirts) are solitary, rather than colonial, but grow in groups, resembling slightly flattened milky white grapes. It may be fouled with other organisms such as hydroids or bryozoans, and may also be covered with silt or sand. The incurrent and excurrent siphons are not spaced very far apart, and are used to filter plankton out of the water and bring oxygenated water into the respiratory organs. When picked up and squeezed, they release water from their excurrent siphon in a tight stream, thus the name “sea squirt.” Individual sea grapes grow to 1 to 2 inches in height.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. This tunicate is one of the most commonly found fouling organisms affecting clam culture equipment. It sets individually on the surface of clam bags and cover netting. Because it binds with others, the sea grape can form dense mats over the entire surface of the bag.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. Individual squirts can be manually removed from the bag surface by hand or brush and will not reattach.

Staghorn Bryozoan

Description

The staghorn bryozoan is a calcareous, encrusting bryozoan, ranging from North Carolina to the Gulf of Mexico, preferring warm waters. It settles upon three dimensional surfaces, such as sea grasses, sea whips and clam bags, forming orange to purple tubular colonies, resembling small clumps of coral. The rectangular body chamber of the individual animals is structurally continuous with that of others in the colony, with each animal enclosed in its own box-like exoskeleton. The feeding apparatus has multiple tentacles contained within this box, which extend and are used to feed on passing plankton.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Bryozoans are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. This bryozoan can attach to clam bags and cover netting, becoming a fouling nuisance.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling on the bags may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. Bryozoan clumps can be manually removed from the bag surface by hand or brush and will not reattach.

Rough Sea Squirt, Pleated Sea Squirt, Brain Squirt

Description

The pleated or rough sea squirt is the largest of the solitary sea squirts, reaching 4 inches in length, and is the most common sea squirt found in the Gulf of Mexico and southeastern U.S, up to North Carolina. They can be found singly or clumped together, often fouling ropes, boat bottoms, pilings and floating docks; but can also be found on grass flats. Being sessile, they often are encrusted with other tunicates or bryozoans. They are a tan color, with a wrinkly and slippery exterior. There are four lobes, as viewed from above, edged with purple-brown lines, and two distinct siphons, one incurrent and one excurrent. They filter plankton out of the water for food and, as with other sea squirts, when picked up and squeezed, they will shoot out a surprisingly long stream of water.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Sea squirts (tunicates) are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. This tunicate sets individually on the surface of clam bags and cover netting, but can also bind together, covering larger areas.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. This tunicate can be difficult to remove from the bag or cover net surface.

Lettuce Bryozoan

Description

Lettuce bryozoans grow as lacy ruffles that are as thin and brittle as a potato chip. Colonies grow on other organisms, such as seaweeds and sea whips, and may also attach to hard substrates. Young colonies begin as crusts but then grow away from the surface. Heads of lettuce bryozoans may exceed 7 inches in diameter.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Bryozoans are filter or suspension feeders and can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. This bryozoan can attach to clam bags and cover netting, becoming a fouling nuisance.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

Clam bags should be inspected to determine the extent of fouling, particularly at lease sites with limited tidal exchange and when water temperatures are high. Extensive fouling on the bags may limit water flow to the clams and could result in suffocation. If it becomes a problem, fouled cover netting could be removed and clean cover netting replaced over the bags. Bryozoan clumps can be manually removed from the bag surface by hand or brush and will not reattach.

Eastern Oyster

Description

This economically important bivalve is very common in intertidal zones in the southeastern and Gulf of Mexico states, and forms large reefs on mud flats and rocks. Oysters can tolerate a wide range of salinities, from estuaries to salt marshes. They can grow to 6 inches in length, with elongate, irregular, asymmetric valves that have sharp edges. Oysters spawn throughout the summer, giving rise to free-swimming larvae that look for suitable hard substrate to cement onto, often times onto an existing oyster reef. In Florida, oysters can reach an edible size of 3 inches in a year or less. Oyster reefs are homes to many creatures, including fish, gastropods (including the predatory oyster drill), other bivalves, polychaete worms, shrimps, and crabs.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Oysters can have a two-fold effect on clams. As a filter or suspension feeder, oysters can compete for the same type of food (micro alga) as clams. They can also attach to clam bags and cover netting and to the clam shells themselves. This can result in mechanical interference and prevent the clam from opening, feeding or burying. Fouling on the clam shell can make them less desirable for marketing. The eastern oyster grows much faster than clams and under the right conditions (lower salinities) can rapidly “take over” a clam bag resulting in clam mortalities due to suffocation. Clam bags which contain a large set of oysters can be difficult to remove from the lease. Often they are not recovered, resulting in the creation of a small oyster “reef.”

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

The best approach to minimize oyster set is to not plant clam bags on hard lease bottoms during peak periods of oyster spawning. Unfortunately, oyster set can occur periodically from April through October in Florida. To minimize fouling on the clams and bags, a clam farmer could add cover netting during periods of peak sets and remove afterwards, basically harvesting the oysters. Note that plastic or rigid cover netting can also “attract” oyster spat and may become the problem. Dipped bags which stiffen the mesh may also provide suitable substrate for oysters. Clam bags fouled with oysters should be removed from the lease as soon as possible. Gloves are necessary when handling bags covered with oysters as they are very sharp and can cause serious injuries.

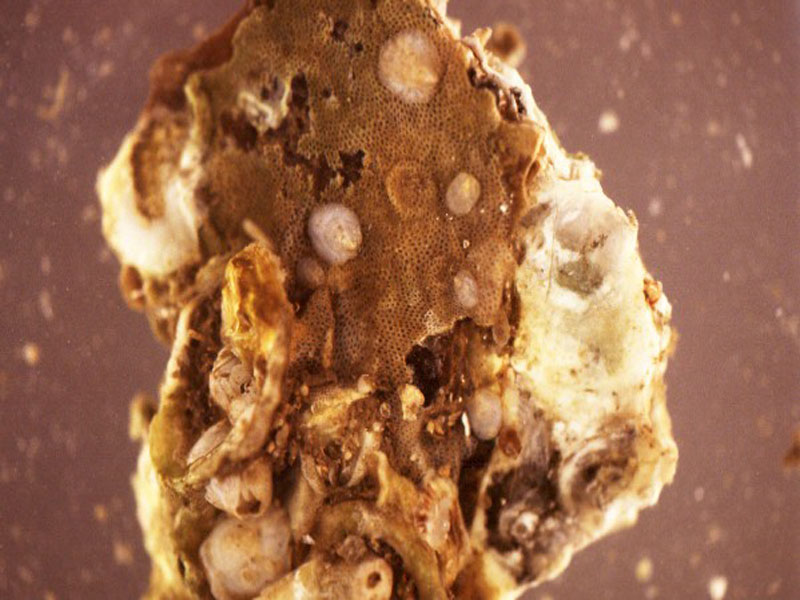

Crested Oyster, Horse Oyster

Description

Like eastern oysters, crested or horse oysters cement themselves to subtidal hard substrates. However, they do not form reefs as do the eastern oysters. Crested oysters live in water that is saltier than that in which eastern oysters live. Shells are circular to oval with wavy (crenulated) margins. The shell attached to the substrate is flat inside, but highly cupped. One way to distinguish crested oysters from eastern oysters is by the row of tiny teeth (denticles) on the inside edge of the upper shell, especially near the hinge. These teeth or more easily felt with a fingertip or knife, than seen with the eye. Adults reach 1 to 2 inches in length.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

Oysters can have a two-fold effect on clams. As a filter or suspension feeder, oysters can compete for the same type of food (micro algae) as clams. They can also attach to clam bags and cover netting and to the clam shells themselves. This can result in mechanical interference and prevent the clam from opening, feeding or burying. Fouling on the shell can make them less desirable for marketing. The crested oyster is smaller than the eastern oyster, does not form reefs and prefers higher salinities.

- FOE

- Competitor

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

To minimize fouling on the clams and bags, a clam farmer could add cover netting during periods of peak sets and remove afterwards, basically harvesting the oysters. Note that plastic or rigid cover netting can also “attract” oyster spat and may become the problem. Dipped bags which stiffen the mesh can also provide suitable substrate for oysters. Clam bags fouled with oysters should be removed from the lease as soon as possible. Gloves are necessary when handling bags covered with oysters as they are very sharp and can cause serious injuries. The crested oyster is less frequently found in and on clam bags than the eastern oyster, and does not pose as great a problem.

Common Atlantic Slippersnail

Description

The slippersnails, or slipper shells, are among the most common gastropods (snails) in shallow waters in the southeastern U.S. They get their name due to a shelf on the inside of the shell, making it look like a slip-on shoe. The common Atlantic slipper shell is a convex shell with a downward curve at the front of the shoe and can form large stacks.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

The slipper shell attaches to the shells of clams, possibly hindering the clam from burying. Also the fouling on the clam shell can make them less desirable for marketing.

- FOE

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

A clam farmer can easily remove slipper shells from the clam shell by popping them off.

Eastern White Slippersnail

Description

The eastern white slippersnail, or slipper shell, is a very common shallow water gastropod (snail), ranging from Nova Scotia to Texas, and found in similar locations as the common Atlantic slipper shell, but is easily differentiated. The white slipper shell is more of a white color, more concave, and flatter than the other. Like the Atlantic slipper shell, it is a herbivore, feeding on macro algae, or seaweeds. It can often be found on the inside of hermit crab shells. This species does not form large stacks. Instead, a small male can be seen atop a large female.

What Are The Effects On Clams?

The slipper shell attaches to the shells of clams, possibly hindering the clam from burying. Also the fouling on the clam shell can make them less desirable for marketing.

- FOE

- Fouler

What Can A Clam Farmer Do?

A clam farmer can easily remove slipper shells from the clam shell by popping them off.