Florida Aquaculture Survey | National Census of Aquaculture | Economic Impact | Background | Industry Components

Shellfish aquaculture in Florida consists primarily of clam farming. However, along the Panhandle primarily in Apalachicola, there are several operations culturing the eastern oyster Crassostrea virginica using extensive methods. Shells are planted on state-owned submerged land leases to attract natural oyster spat. There are 500 acres of shellfish clutch leases formerly granted under Chapter 370, Florida Statutes. The oyster fishery failures in 2012-14 resulted in renewed interest in oyster culture with existing clam leases being modified to allow for water column activities (see Oyster Culture for additional information).

Currently, the clam farming industry supports about 250 growout operations on 1,500 acres of state-owned submerged lands issued under Chapter 253, F.S., off of 12 coastal counties. The naturally warm temperatures and high productivity levels of Florida waters create a superb environment for growing clams. Growth of the northern hard clam Mercenaria mercenaria is almost year round, resulting in a half to a third of the crop time realized in other clam-producing states. In addition, Florida clam growers are able to plant seed year round, enabling them to harvest product continuously. As a result, clam production has increased rapidly over the past 20 years.

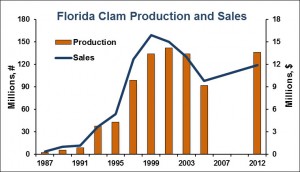

The rapid expansion of the clam culture industry is reflected in the results of aquaculture surveys conducted every other year by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). Production of 2.4 million clams was first reported in 1987 by 13 growers. Twelve years later, 351 growers reported over 134 million clams produced in 1999. Corresponding farm gate, or dockside, sales also increased with a value of $16 million reported. The industry was negatively impacted by the hurricanes of 2004-5 with production and sales in 2005 declining to 92 million clams and $9.8 million, respectively. Surveys were not conducted in 2009 or 2011 due to budgetary constraints.

The rapid expansion of the clam culture industry is reflected in the results of aquaculture surveys conducted every other year by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). Production of 2.4 million clams was first reported in 1987 by 13 growers. Twelve years later, 351 growers reported over 134 million clams produced in 1999. Corresponding farm gate, or dockside, sales also increased with a value of $16 million reported. The industry was negatively impacted by the hurricanes of 2004-5 with production and sales in 2005 declining to 92 million clams and $9.8 million, respectively. Surveys were not conducted in 2009 or 2011 due to budgetary constraints.

In 2012, the NASS Florida Field Office conducted a Florida Aquaculture Survey. Results from this most recent survey indicate that the clam aquaculture industry rebounded from the hurricane-impacted years. However, sales value reflected the downturn of the economy and reduced prices received by clam growers and wholesalers. Highlights of this survey include:

The first national census of aquaculture was conducted by the USDA NASS in 1998. Florida was identified as a leading producer of cultured clams (by volume, not value) with 221 growers reporting $9.5 million in sales. In the 2005 census, Florida fell behind Virginia and Connecticut but led the nation in the number of clam farms with 154 growers reporting $10.7 million in sales.

The most recent Census of Aquaculture was conducted in 2013. Highlights of this census include:

In addition to the number of farms, there are many spin-off businesses that have developed in support of the clam aquaculture industry. For instance, there are hatchery operators who produce seed for growers, seamstresses who make clam bags, boat builders who specialize in clam work skiffs, and manufacturers who produce harvesting and processing equipment. Shellfish wholesalers purchase clams from growers, add value, and distribute to markets nationwide. The industry also provides local employment, such as processing plant workers and truck drivers. Thus, the economic impact is much larger than the farm gate sales values reported above. University of Florida economists surveyed certified shellfish wholesalers in 1999 and, again, in 2007 to determine the number and value of clams handled in those years to estimate direct, indirect, and induced impacts. The contribution of cultured clam sales was assessed to be $34 million to the state’s economy in 1999, increasing to $53 million in 2007, making clam farming an important agribusiness.

The most recent study of the economic contribution associated with the Florida clam industry was conducted in 2012. Highlights of this economic impact study include:

Shellfish aquaculture is a relatively new pursuit in the state. Yet, in just over three decades, hard clams represent the single most important aquacultured food item produced by Florida’s aquatic growers. This industry traces its beginnings to the Indian River lagoon along the east central coast. During the 1980s, unreliable sets of hard clams prompted harvesters to investigate aquaculture as an alternative to fishing natural stocks. This transition was facilitated by research conducted at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution, in which traditional culture techniques used in the Northeast were modified for Florida’s subtropical, subtidal conditions. At the same time, state-funded educational programs introduced the general public to the prospects of shellfish culture. Expanding employment opportunities for the Florida fishing industry affected by increasing regulations was the focus of federally-funded job retraining programs conducted during the 1990s. These community-based programs provided the infrastructure for introducing shellfish aquaculture as a means of economic growth for rural communities. Over 350 program graduates were placed onto shellfish aquaculture leases of 2-4 acres, the first leases to be approved along the Gulf of Mexico coast. The state’s progressive leasing program was the result of the Florida legislature declaring it to be in their economic, resource management, and food production interests to promote aquaculture production by leasing state-owned submerged lands.

Changing Seas – Farming the Seas, Part 1, Produced by WPBT2 Miami

Cedar Key Clams: Fishermen Farming the Sea, Produced by UF IFAS

The components of clam farming consist of three consecutive biological or cultural stages—production of small seed in a hatchery, rearing of larger seed for field planting in a land-based nursery, and growout on an openwater lease to a marketable size.

Hatchery: Clam culture begins in the hatchery with the production of seed. While hatchery techniques are well defined, they are fairly complex. In addition, a hatchery operation requires a capital investment in property, facilities, equipment, and skilled labor. For these reasons, most growers prefer to purchase seed from a hatchery. There are 8-10 hatcheries in the state, ranging from small backyard operations to commercial-sized facilities, which provide almost a half billion seed annually. In the hatchery, adult clams, or broodstock, are induced to spawn by manipulation of water temperatures. Fertilized eggs and resulting free-swimming larval stages are reared under controlled conditions in large tanks filled with filtered, sterilized seawater. Cultured marine phytoplankton, or microalgae, are fed at increasing densities during the 10 to 14-day larval culture phase. After which, pediveliger larvae begin to settle out of the water column, or metamorphose. Even though a true shell is formed at this time, post-set seed are microscopic and vulnerable to fluctuating environmental conditions. They are maintained in the hatchery for another 30 to 45 days in downwellers until they reach about 1 mm in size.

Nursery: This component serves as an intermediate stage and provides the small clam seed produced in a hatchery with an adequate food supply and protection from predators until they are ready to be planted for growout. Nursery systems built on land usually consist of wellers or raceways. A weller system consists of open-ended cylinders placed in a water reservoir. Seawater circulates through the seed mass, which is suspended on a screen at the bottom of the cylinder. The direction of the water flow defines whether the system is referred to as a downweller or upweller. Raceways consist of shallow tanks or trays with salt water pumped from an adjacent source providing a horizontal flow as opposed to a vertical flow in the wellers. The water flow provides food (naturally occurring phytoplankton) and oxygen to the seed. Many growers are attracted to the nursery option as seed costs are lower and, at times, smaller seed are more available. Further, the systems can be constructed inexpensively and maintained on a part-time basis. Depending on water temperatures, 1-2 mm seed require from 6-12 weeks to reach 5-6 mm in shell length, the minimum size planted in the field. Currently, about 40 land-based nursery facilities are located statewide. These systems can be novel, such as floating upwellers or FLUPYS, which are employed at specific sites, usually marinas.

Growout: Hard clams are grown on estuarine or coastal submerged lands leased from the State of Florida. Successful clam farming requires good water quality, free of bacteriological and industrial contamination. The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Aquaculture administers the lease program and monitors coastal waters for shellfish harvesting classifications. The lease is for a 10-year term and is renewable and transferable. The lessee pays an initial application fee and an annual rental fee thereafter. In addition, the leaseholder must plant a minimum of 100,000 clam seed per acre per year to fulfill their agreement.

Since clams are bottom-dwelling animals, growout systems are designed to place the seed in a bottom substrate and provide protection from predators. The system must allow substantial water flow to provide both oxygen and natural food, or phytoplankton, for growth. Most growers in the state use the soft bag, which is made of a polyester mesh material. The bag is staked to the bottom using a variety of materials, such as PVC pipe. Bags are typically “belted” together in units of 5 to 10 and planted in rows on the lease. Naturally occurring sediments provided by tidal action and currents, as well as the digging activity of the clams, allow the bag to become buried in the bottom sediments. When harvested, only the product and mesh bag are removed from the bottom. A winch or roller rig operated from the boat assists in harvesting the bags.

The bag culture method usually involves a two-step process. The first step involves field nursing seed, minimum size of 5-6 mm (1/4 inch) in shell length, in a small mesh bag. Typically, about 10-15,000 seed are planted in a 3 to 4 mm mesh bag with the dimensions of 4 feet by 4 feet, or 16 ft2. When the seed reach a size of 12-15 mm (1/2 inch), usually after 3 to 6 months, they are transferred to the final bag size, which may range from 9 to 12 mm in mesh size. The larger seed are stocked at a lower density at rates from 800 to 1,400 per bag (50-85/ft2). A crop of littleneck-sized clams, which are one inch in shell width, can be grown within 12-18 months depending on water temperatures and food availability. Survival rates are specific not only to planting methods and experience, but also predator abundance. Additional cover netting, such as galvanized wire or plastic netting, placed over the bags is required in some growing areas. Crabs, snails, rays, fish, and humans are among the many predators that contribute to mortalities. Another culture method, traditionally used in the Northeast, is now being used by growers on the east and southwest Florida coasts. The bottom plant method places a single layer of cover netting over the broadcasted seed.

Once clams are harvested, they are delivered by the grower to a certified shellfish wholesaler. At the wholesaler’s processing plant, clams are prepared for market by washing, sorting, grading by size, counting, packaging, and tagging. Clams are generally sold live, or as shellstock, and refrigerated trucks are used in transporting product to marketplaces throughout the state and nation.